A juvenile court (or young offender’s court) is a tribunal having special authority to pass judgements for crimes that are committed by children or adolescents who have not attained the age of majority. In most modern legal systems, children or teens who commit a crime are treated differently from legal adults that have committed the same offense.

Industrialized countries differ in whether juveniles should be tried as adults for serious crimes or considered separately. Since the 1970s, minors have been tried increasingly as adults in response to “increases in violent juvenile crime.” Young offenders may still not be prosecuted as adults. Serious offenses, such as murder or rape, can be prosecuted through adult court in England.However, as of 2007, no United States data reported any exact numbers of juvenile offenders prosecuted as adults.In contrast, countries such as Australia and Japan are in the early stages of developing and implementing youth-focused justice initiatives Positive_youth_justice as a deferment from adult court.

Globally, the United Nations’ has encouraged nations to reform their systems to fit with a model in which “entire society [must] ensure the harmonious development of adolescence” despite the delinquent behavior that may be causing issues. The hope was to create a more “child-friendly justice”. Despite all the changes made by the United Nations, the rules in practice are less clear cut. Changes in a broad context cause issues of implementation locally, and international crimes committed by youth are causing additional questions regarding the benefit of separate proceedings for juveniles.

Issues of juvenile justice have become increasingly global in several cultural contexts. As globalization has occurred in recent centuries, issues of justice, and more specifically protecting the rights of children as it relates to juvenile courts, have been called to question. Global policies regarding this issue have become more widely accepted, and a general culture of treatment of children offenders has adapted to this trend.

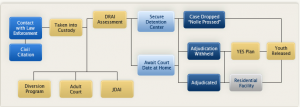

Youth under the age of 18 who are accused of committing a delinquent or criminal act are typically processed through a juvenile justice system. While similar to that of the adult criminal justice system in many ways—processes include arrest, detainment, petitions, hearings, adjudications, dispositions, placement, probation, and reentry—the juvenile justice process operates according to the premise that youth are fundamentally different from adults, both in terms of level of responsibility and potential for rehabilitation. The primary goals of the juvenile justice system, in addition to maintaining public safety, are skill development, habilitation, rehabilitation, addressing treatment needs, and successful reintegration of youth into the community.

According to a Home Office study, one out of four teenagers could be classified as a serious offender, with high potential to become a criminal . The 2003 crime and justice survey suggests that there are 3.8 million “active offenders” in England and Wales . Government and the society always hope that these young offenders would grow out of their crimes eventually. But this may not be the case under all circumstances.

There are a large number of exceptions where they become bigger criminals posing higher threats to the society. Offence by teenagers is much higher than it was estimated. It is also a fact that many of these potential criminals start with a humble beginning in the early teens. A Home Office study says that 57% of the male population between 12 and 30 have committed at least one crime . This obviously does not mean that the girls are not offenders at all. They can claim an equal success in crime. They start quite early on drinking, drug addiction, shoplifting, prostituting, buying stolen goods knowingly, causing criminal damage to public property etc. Both boys and girls involve in serious fights, thieving at work places, foul mouthing, insulting and offensive language, ridiculing and indulging in racist offences.

Youth justice system

In the last hundred years, juvenile justice is concentrating on punishment and welfare both. England earlier had the unfortunate system of juvenile justice of imprisonment, transportation and even death penalty, regardless of the age of the offender. Now children and adults are treated differently and juveniles have their own courts to try their offences. A large number of them are considered to be suffering from behavioural disorders and in such cases, they are sent for psychiatric treatments and psychotherapies. The Punishments are milder keeping in view of the offence and the age of the offender and his responsibility in the crime. The most important point here is the welfare of the child and delinking him from later life offences .

Children Act 1908, Children and Young Persons Act 1933, Criminal Justice Bill, 1948, Children Act 1948, Children and Young Persons Act, 1969, and Children’s Act, 1989, steadily passed various beneficent laws for the children. Young offenders naturally have to be treated with care, as they might not be fully responsible for their crimes and their future should never get marred due to a crime committed when they are still juveniles. Over the years, the stress has shifted from punishment to welfare with more planning for their adult life. Condemnation of the crime has been steadily becoming milder and concern for the adult life had been growing.

Today juvenile crime is being treated as a social melody. Records are not only maintained by the Police, but also by the Social services Police and Social Services work from many angles now. Finding the family, gaining the cooperation of the family, trying to contact the child as often as possible even after he returns home, interviewing the rest of the family trying to locate the source of the problem, establishing an interview schedule, insisting on a self-reporting system have all become part of the welfare process of a child offender. Arrests are made only under unavoidable circumstances and most of the arrests result in letting off the child with a warning, without charging in the hope that it might dishearten the youngster from launching into a career of offences. Ethnic background, family circumstances, possible abuse at home or outside, mental deficiencies and racial discrimination are all evaluated while providing a long-term social care.

A recent addition is Crime and Disorder Act, 1998, which addresses the persistent young offenders, according to which the police or local authority can apply for an Anti Social Behaviour Order from a magistrate court when a child is above ten and is distinctly anti-social and this order will be in force for two years and more. This depends on the eligibility of circumstances and other measures need not have been exhausted.

Child Curfew Schemes work on dual purpose, where they discourage children to be on the street at night and protect citizens from the hooliganism of such children. In June 2000, Child Safety Order came into being to place a criminal minded child lesser than ten under the supervision of a social worker. The Detention and Training order (Sections 73-79) provides new custodial sentences that could prevent further crimes .

Under Final Warning Scheme, 10 – 17 year olds are given final warnings, instead of repeat cautioning. Since June 2000, Parenting Orders enable the Magistrate’s Court to pass an order on the parents of a perpetually offending youngster urging them to control their offender child by attending to school and stay at home under parental supervision. Being out in the night could place the youngster in danger of being exploited by pimps, drug sellers, criminals and murderers. Reparation Orders insist that the offending youngster, according to the seriousness of the offence committed, would render reparation of 24 hours to the victim or community at large directly or indirectly, within three months of committing the offence, mostly in the form of a letter of apology, clearing graffiti, personally apologising, or repairing the criminal damage in suitable way. Truancy Powers are used by the Police to track down offending youngsters with the help of school or local authority. Truancy has been perceived as a definite path to criminal life.

Crime and Disorder Act, 1998, provides many more tools of justice and welfare to young offenders and to the community. Section 37 focuses on the duties, functions of the justice practitioners to prevent the youngsters from offending and reoffending. Section 38 establishes the duty and cooperation of local authorities, social services, educational institutions, police and other Youth justice services .

Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999, has brought in a few more changes into youth justice. Youngsters who have pleaded guilty and those who are first-time offenders could be referred to a youth offender panel, which would concentrate on reforming the youth. Many measures towards restorative justice like integrating with family and community, reattending the school, assuming responsibility of guilty behaviour, and these are increasingly becoming part of justice meted out to the offenders.

Witness protection, especially underage witnesses, sometimes even with mental and physical handicaps, are screened, hidden from the offender, or witnessing on television, emptying the court room during witnessing, clearing the courtroom or giving banning orders to journalists who are warned against breaching the privacy and could be prevented from publishing details, video conferencing with the witnesses, allowing pre-recorded tapes as evidence and special communication facility for physically impaired witness or offender came into existence depending n this Act. Disengaged youngsters get into criminal life easily and the new justice and reforms are encouraging youngsters either to pursue their education further, or get themselves employed for the personal good and for the good of the community at large.

Today’s Youth Detention Centres have full sized arcade game consoles, TVs, computers and furnished rooms and according to reports they are treated incredibly well, in the hope that they would come out of their offensive habits and become responsible members of the society. The spoiling has gone to the extent of drawing criticism from the public that instead of learning any lessons, most of the youngsters are becoming more destructive and foul-mouthed!

Offenders are tested for drugs regularly and psychological help and guidance is rendered as part of the rehabilitation process. Personal advisers are provided. Employment training seems to have shown remarkable possibilities. Researches on the family background, homelessness and links between Dyslexia and crime go on relentlessly trying to better the understanding of young offenders. In 2002, July, Home Secretary unveiled new measures according to which, offenders between 10 and 11, who are too young to be imprisoned, would be remanded instead in high supervision foster placements. Round the clock specialist support, permission and encouragement to continue contact with family and friends are provided through National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders. Therapeutic counselling for sexual offenders is given with better results. The Youth Court that started operating in October 1992, started issuing custodial sentences had been a resounding success . Majority of these sentences were of three months or less. Youth courts tend to be less formal than the adult courts. The recently introduced counselling and interviewing had been of immense help in establishing and understanding the background of the offender, and with psychological help, in most of the cases, the possible motive, reason or excuse too could be found out. Drug use, another terrible menace, too could be detected from the interviews or studies . The last decade of the century had not been particularly encouraging where youth crimes are concerned . Separate facilities are created for female offenders, as they always stand in need of protection from their male counterparts. Sentencing does not target only on the welfare and guidance for the youngster, but also on the community that has to be protected from the offenders and this includes offences of racial discrimination .

Community mediation centres are viewed as part of the cultural service today. They try to work on the principle of elimination of bad company, one of the many factors that take a child into criminal life. Much is expected out of professional treatment and effective counselling with positive and supportive atmosphere. Balanced daily activities have proved to be beneficial on young and impressionable minds. There is a stress on moral development and moral education in modern societies.

It was reported in September 2004, that Government would bring the young offenders faster to justice . Government has been continuously working in reducing the crime of juveniles and their rehabilitation with single-minded determination. There is remarkable improvement in handling the court cases with all professional help in place . The Youth Justice Board has funded many programmes that are designed and conducted to prevent juvenile offending. Many programmes on drug and alcohol abuse, safe sex, education on HIV and importance of school and later, University education have all been conducted. They also conduct programmes with the intention of humanising the youngsters and steer them away from the path of crime. In this direction, apologising and compensating the victims of the offence has created certain goodwill in the community. Frequent assessment of all the connected agencies have kept them as efficient as possible. They are also subjected to continuous scrutiny due to the ongoing researches and surveys.

Government has done not only adequate work, but also work that could be classified more than necessary. If one goes through the various reports carefully, some of them positively regret the indulgence with which Government is approaching this issue. One of the reports regretfully points out that juveniles are so thoroughly spoilt that instead of improving, they are becoming downright offensive. They treat the staff with great disdain, ridicule them and try to get away with cheeky and disturbing behaviour only because of their age. Most of them show absolutely no desire to change and insist on remaining uneducated and ignorant. The facilities provided by the Government are so adequate that they try to return to the same centres again and again. They also achieve in making friends with likeminded counterparts. Most of the families want them to return to the same place, to avoid unpleasantness at home. The family would have moved on and it would also have been difficult to provide space for the juvenile with dubious records. Sometimes, they have to think about the other children. Some parents fear the immoral effect an offender child could have on other children of the family and wishes to keep the youngster far away from the other children which is understandable.

This picture is definitely a hopeless one; but there are other encouraging reports, where they accept that the recent laws had been very helpful in reforming some of the offenders. Still it cannot be denied that amongst some of the offenders reoffending is steadily increasing. Behaviour in care centres, usually ends up with the offended offender throwing the TV at the wall and very patiently, the authorities replace it with a brand new TV! Perhaps the offenders should be treated with a little more discipline, without making the place so desirable, that an offender would nostalgically return there again and again!

Government insists on better and more involved role of Schools and families in the welfare of the child. It is not possible to guide the child through a third person, that is, at the moment, is the Government. Child requires emotional and friendly ties at home and society and this could be provided by parents, peers and schools. However hard the Government tries to fill in that place, it would never be possible for its agencies to do so. Emotional ties, culturally developed since birth at home and in the community, are absolutely important for any human being, however individualistic we are today. Hence, the duty lies with friends, schools and family and if they provide adequate support to the offender, it would not be very long before he starts responding. So, young offenders cannot be the responsibility of Government alone.

It should not be assumed that dealing with the young offenders, punishing them with understanding, dealing with their various backgrounds and reforming them are matters of ease and comfort. They could become downright offensive in their ignorance and newfound importance. They are too young to realise that the justice agencies are bending backwards to please them and facilitate them only because of their determination to cure them of all evils. There are instances, when a juvenile offender became singularly dangerous. There are also pathetic and disturbing instances when these unhappy souls get into the mood of self-harming. With the right attitude created by thoughtful laws, Government should be able to bring down the number of offences steadily, and succeed in making these youngsters part of the society. Community’s role is not small either. Great support, understanding and empathy should be shown by the community.

Another agency that could be enormously helpful in juvenile justice is media. Instead of dishing out sensational stories and make the offender popular throughout the islands, it would be a great help if such budding criminals receive as less attention from the media as possible. What the offender of tender age needs is understanding, sympathy and sensitivity from all quarters. If media takes up a vengeful attitude targeting the offenders without restrain, it would not take very long for the offender to turn into a bigger criminal. If Government has to bring more legislations, they should find a way of restraining the media at necessary quarters, instead of allowing it to work unbridled in the name of ‘freedom of the press’, which might become a crucial negative point for the freedom of ordinary people. This mainly applies to the family of the juvenile offender that would be marred for generations for no particular fault of theirs.

Bibliography

- Annika Snare, Ed., Youth, Crime and Justice, (Oxford University Press, 1991)

- T. Ferguson, The Young Delinquent in his Social Setting, (Oxford University Press, 1952)

- J.A. Walter, Sent away, A Stud of Young Offenders in Care, (Farmborough, Teakfield Limited, 1978).

- John Pitts, Working with Young Offenders, (Hampshire: British Association of Social Workers, 1999).

- Roger Graef, Living Dangerously, (London, Harper Collins Publishers, 1993).

- David McAllister, A Keith Bottomley, Alison Leibring, From Custody to Community: Throughcare for Young Offenders, (Aldershot: Avebury, 1992)

- David O’Mahony and Kevin Haines, An Evaluation of the Introduction and Operation of the Youth Court, (Home Office Research Study, 1996)

- Maggy Lee, Youth, Crime and Police Work, (Hampshire, Macmillan Press Ltd., 1998)

- Ann Hagell and Tim Newburn, Persistent Young Offenders, (London: Policy Studies Institute, 1993).