Introduction

The current dispute settlement system was created as part of the WTO Agreementduring the Uruguay Round. It is embodied in the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes, commonly referred to as the Dispute Settlement Understanding and abbreviated “DSU” (referred to as such in this guide). The DSU, which constitutes Annex 2 of the WTO Agreement, sets out the procedures and rules that define today’s dispute settlement system. It should however be noted that, to a large degree, the current dispute settlement system is the result of the evolution of rules, procedures and practices developed over almost half a century under the GATT 1947.

Explanatory note: The annexes of the WTO Agreement contain all the specific multilateral agreements. In other words, the WTO Agreement incorporates all agreements that have been concluded in the Uruguay Round. References in this guide to the “WTO Agreement” in general, therefore, include the totality of these rules. However, the WTO Agreement itself, if taken in isolation from its annexes, is a short Agreement containing 16 Articles that set out the institutional framework of the (WTO) as an international organization. Specific references to the WTO Agreement (e.g. “Article XVI of the WTO Agreement”) relate to these rules.

In the present era of globalization, countries seek strengthened security as regards economic relations Vis-a-vis other members of the international system. With the expansion of transporter transition among counters since early 20th century, members of the international community have found themselves intrinsically involved in more and more trade related disputes with each other. While such dispute can be attributed, on the one hand, to arbitrary exercise of power and dominance by a handful of developed countries dissatisfaction over the existing rules and procedures governing inter — state economic relations has also contributed to a large extent to aggravate the situation further, With such relations, countries overwhelmingly felt the need of finding a common ground to resolve any such disputes posing threat to destabilize the state of their economic affairs.

A regulatory framework for international trade is the sum of actions taken by the members of the international community with a view to facilitate trading among nation by resolving all conflicts and misunderstandings that many pose threat to jeopardize their economic relations. One of the fundamental impacts of such disputes is the impairment of trade relations. One of the fundamental impacts of such disputes is the impairment of trade relations. One of the Fundamental impacts of such disputes is the impairment of trade relationship between private parties, private party and state and inter-state trade relationship (ICC-B2004). The WTO’S dispute settlement system is a quite novel international jurisdictional process in this regard. Although the General Agreement on tariffs and trade GATT), the precursor of the WTO, also had this feature, it is the uniqueness of the WTO regime that clearly draws the line of difference between the two regimes.

While the establishment of the WTO, as a result of the Uruguay round negotiations epitomizes a landmark achievement in designing a set of disciplines and commitments as to enhance trading relations among nations, the adoption of the understanding on rules and procedures governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU) is perhaps the most important of them all another significant point of departure from GATT to WTO is that members are no longer Contracting parties; rather they are bound by the unique trait of single undertaking the WTO evolves as a rules based system rather than a consensus based one.

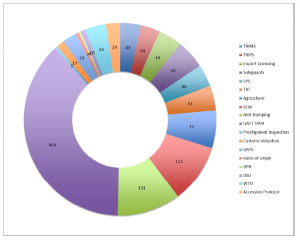

With the increasing number of disputes threatening horizontal sustainability of economic relations among the WTO members, the question regarding authoritative power and efficacy of the WTO-DSM haunts the minds of many. Since the establishment of the WTO in 1995, as many as 324 complaints (relating to both trade remedy measures) have been brought to the DSB till end-2004. Majority of these complaints were placed by the developed countries with the USA, the EC and Canada being the top three complaints, it is, therefore, of much concern for the developing and least developed members of the WTO to understand the rules of game in the DSM, particularly when their interest is at stake. It may. however, be noted that the LDCs are yet to resort to the DSB in a substantive manner. Bangladesh has so far been the first LDC to file a complaint with the DSB. Before embarking upon the core section which will deal with the state of LDC and developing country interests in the WTO-DSU, a brief overview of the dispute system under both the GAIT and WTO will be quite helpfiil in understanding the nitty-gritty of the matter.

Dispute Settlement under the GATT System

The provision for settlement of dispute were laid down in articles XXH (Consultations) and XXIII (Nullification and Impairment) (!) A brief look at the GATT dispute settlement system indicates the following administrative phases adopted with a view to settling down any dispute.

- The Chairman of the contracting parties: The initial investigative responsibilitywas vested upon the Chairman.

2 A trade dispute brought under the DSU deals with government actions concerning trade rights rather than with private rights, e.g. the TRIPS agreement.3 Under the GATT system, members were termed Contracting Parties. 4 WTO website: 2004, 5 No. of complaints by; US-81, EC-64, and Canada-26. 6 The lead Acid Battery case with respect to India’s imposition of Anti-Dumping Measures (DS306).

- Working party: The matter, after being dealt with by the chairman, was referred to a working party for detailed examination. Such working parties were responsible for conciliation and compromise: it did not play any adjudicative role. Moreover, over time, skepticism began to grow as regards objectivity and impartiality of the working party. This apprehension, coupled with the increasing complexity of the subjects of disputes, compelled the contracting parties to go for the penal system.

Panel system: The penal system fulfilled, to some extent, the need for a quasi judicial system. Though the initial practice was to appoint sessional penal, appointment of ad hoc panels replaced the exercise in 1955. These ad hoc panels consisted of three to five individuals representing countries having no direct interest in the dispute.

It needs to be mentioned here that the GATT provision, at the initial stage, permitted the contracting only. Parties, however, increasingly felt the need of going beyond this structure. Subsequently, in 1958; the procedures for consultation under Article XXH were adopted allowing-third parties, nevertheless, one major flaw persisted with the system: tendency to treat consultations as private affairs, (narayan 2003).

Tough the contracting parties aspired for a practical system to bring end to any dispute, reports of both.

The working part} and the panels were treated as advisory opinions only. The provision of legal binding as regards implementation of these reports were completely absent in the GATT provision.

Dispute settlement proceedings in the WTO

Toeing the legitimate quasi-judicial authority under the WTO, the DSB performs according to a defined set of rules and procedures. Starting with filing an application for consultation, a number has to go through a series of legal proceedings until the final rulings is implemented. The various phases of WTO DSB proceedings are briefly discussed here.

Consultations

The consultation phase is aimed at bringing about amicable resolution to disputes. As has been laid down in Article 4 of the DSU, a Member to whom a request for consultation is made must response within 10 days and consultations must be entered into within 30 days. Maximum timeframe for reaching an agreement through consultation is 60 days. Failing to this, the complaining party can request for panel. It may, however, be noted that consultations may last for a longer period as the initiative to request for panel establishment lies with the complaining party. Country (ies) haying substantial interest in the matter may submit written request to the DSB for joining the consultations as third party (ies).

Panel Request

Establishment of panel, upon the request by a complainant, is guaranteed by the provision of negative or reverse consensus. This implies that a panel request can be turned down only if all the DSB members decides so, by consensus. As the complainant itself is a member of the DSB, panel formation is automatic,

Panel Composition

A DSB Panel consists of three to five members. The secretariat produces an indicative list of qualified governmental and nongovernmental candidates maintained by the secretariat. Parties to the dispute have the right to object to proposed names only for compelling reasons. Falling to confirm the names within 20 days of panel establishment, the WTO Director General, upon request by earlier party, can choose the panel members.

Panel Composition

A ‘DSB panel generally takes six months to issue its final Report. During this period, the process consists of written pleadings from both the parties to the dispute and the third party (ies), a first oral hearing at which both parties and third party (ies) are heard, and a second hearing excluding the third party (ies). This processes meant to be over within four months. As for the preparation of a report by the panel, it is mandated to “make an objective assessment of the matter before it including an objective assessment of the facts of the case and the applicability of and conformity with the relevant covered agreements”. This includes an interim report and the final report Either party has the right to appeal against the final panel report,

Adoption of panel Reports

If not appealed, the Panel report is to be adopted by the parties within 60 days of it being circulated. Though the option lies for the DSB not to adopt the report by consensus, It is again the negative or reverse consensus that guarantees the adoption.

Appeal Procedures

The appellate Body (AB) is a standing body composed of seven individuals appointed for four year terms by the DSB. Once an appeal is brought the procedures before the AB consists of a written pleading by the appellant, a written response by the appellee and written submission and notification from third parties. An oral hearing by the appellee and written submission by the parties come next. The stipulated time limit for the whole procedure is 60 days (90 days in exceptional circumstances) from the date of filing the appeal to the date the AB report is delivered. The jurisdiction of the AB is limited to “issues of law covered in the panel report and legal interpretations developed by the panel”. The AB report is to be adopted within 30 days of circulation. Such adoption entails adoption of those portions of the panel report not appealed.

Implementations of AB Report

Once adopted, the report is to be “unconditionally accepted by the parties to the dispute”. However, an extended timeline may be allowed if the responding party finds it impracticable to comply immediately with the recommendations. Previous examples show that up to 15 months have been allowed to the responding parties to comply with the Panel or AB decisions.

Compensation/Retaliation

In the event of non-compliance, by the responding parties, with the DSB decisions the complaining party has been allowed to go for compensation or resort to retaliation. These, however, are temporary measures. If the disputant parties fail to agree on mutually acceptable compensation, the complaining party may request the DSB for light to retaliate. Retaliation generally takes the form of withdrawal of concessions i.e. imposition of additional customs duties on products originating in the responding country.

Arbitration

Arbitration lies at the bottom of dispute settlement procedure. When a responding party objects to the level of sanctions imposed against it the complaining party, with authorization from the DSB, may refer the matter to arbitration.

These various phases of the DS procedures, by practice, consume a great deal of time to bring an end to any dispute. Thus one might speculate the causal effects of such time lagging procedures particularly when an LDC is involved in such disputes. One has to understand that trading of good in question remains suspended until a solution is reached upon. Hence, the economic impact of such lengthy procedures can sometimes by more devastating than the loss supposed to be incurred by the complaining party had. it not resorted to the DSB

Basic: Features of the DSB.

Issues of Concerns for Developing Countries

There is no denying the fact that the LDC party will suffer the most, in terms of trade and economic impact of a measure in dispute, then the developed country party which is likely to be modestly affected. This can be attributed to the understanding that actual trade impact of measures involved in disputes, likely to be brought by or against LDC members, will almost certainly be small relative to the total trade of a developed country party to the dispute. The Panel/AB procedures of the DSU are both too cumbersome and too costly to warrant their use for small volumes of trade.

What is, therefore, important is to take note of all inconsistencies (from the LDC perspective) existing in the DSU provisions and head away with scrupulous thoughts to bring in necessary amendments in the system. In view of the above, the following discussion might be of particular concern.

Outline of Dispute Settlement for Developing Countries

It has been discussed earlier that efforts to review the procedural settings of the DSU and bringing about required amendments to existing texts have not been achieved up to the mark of expectation. In light of this difficulty, LDC Members should seek a solution within existing provision to the fullest extent possible. This objective can be addressed through existing DSU provision. ‘The LDC members’ position will be supported by provisions in Article 3 – General Provision; and 21 Surveillance of Implementation of Recommendations and Rulings,

The LDC Members’ objectives will be to obtain agreement to establish a special track for dispute settlement involving them either as complainant or respondent (Browne 2004). LDC members may put forward the following recommendations.

1) Consultations (in accordance with Article 4) shall take place in the LDC Member’s capital city. The venue may, however, be changed if the LDC Member proposes so; the location will be agreed between the parties in such cases.

2) If consultations fail to resolve the dispute within the stipulated 60 day timeframe, the Director-General shall provide conciliation pursuant to Article 5. This process shall start with shall provide a comprehensive briefing, by the secretariat, on the legal, historical and procedural aspects of the matter in dispute to the – Parties and the conciliator. The conciliator working closely with the parties to the dispute, will establish the facts of the dispute, examine the claims of both parties, clearly define the issues of the dispute and, taking all relevant factors (including special attention to the particular problems of the LDC Member) into account, submit non-binding proposals for a possible settlement to the parties. This whole process should take no longer than 60 days.

3) If the parties are unable to resolve the dispute on the basis of the conciliator’s recommendations, the matter shall be arbitrated expeditiously pursuant to Article 25. Standard procedures will be established by the DSB, with a tight timeframe, e.g., maximum 60 days.

4) If the measure in dispute is found to be inconsistent with WTO obligations, the application of the measure shall be suspended [vis-a vis the complainant] to the extent of its inconsistency within 60 days, pending its withdrawal or its modification to bring it fully into compliance with WTO obligations.

5) If the inconsistent measure was applied against the trade of an LDC Member by a developed country Member, then, in addition to withdrawing the measure, the latter will pay sufficient monetary compensation to revitalize the firms in the LDC Member’s territory that suffered severe commercial losses as a result of the measure Such compensation shall not exceed the value of trade lost as a result of the contested measure. Any disagreement regarding the value of such compensation will be referred to the arbitrator (acting in stage 3) for fesolution within 60 days.

Some Change is required for developing Countries

In view of the above, it is thus in the greater interest of the LDCs to strive for an enhanced dispute settlement procedure aimed to protect their interest. Having discussed various articles of the DSU. as have been provisioned in the WTO agreement, the following pouits might be identified:

- Panel process is too complex for LDCs particularly in terms of capacity to address the issues vis-a-vis the developed and developing members.

- Panel process is extensively tune consuming for firms in LDCs to survive when their trade has been disrupted by measures in dispute.

- Relief provided by DSU procedures does not recover commercial and economic losses suffered by mollification and impairment of benefits.

- A good number of the S & D provisions for LDC Members are soft law, i.e. lack provision of mandatory compliance by the developed members.

- Panels and the AB will apply hard law criteria to soft law S&D provisions thereby nullifying their potential benefit

- Arbitration are more likely to take account of soft law provisions, at least for guidance.

- Consultations, ‘good offices’ and arbitration can be less complex, less expensive and briefer than the panel process.

- Developed county Members may have difficulties extending soft law S&D provisions to developing country Members because they are not a homogeneous group, but all LDC Members deserve S&D benefits, if they are to be able to use the dispute settlement system.

- It will be easier to make progress working within existing WTO and DSU provisions than seeking extensive amendments.

Technical Assistance for Capacity Building

It is, therefore, undisputable the LDCs do lack the capacity to engage into the WTO dispute settlement procedure. Though the financial ability is of a major concern for these economically restrained countries, both negotiating and legal expertise in dealing with the complex DSU.

Issues further aggravate the situation. Moreover, there is hardly any academic institute in the LDCs which offer such specialized courses like Trade Policy and Commercial Diplomacy, particularly at the tertiary level, for students, academics and trade experts. It is in this need that WTO members came up with various plans to provide assistance to the LDCs to strengthen their position as regards DSU proceedings. Following is a description of such facilities available for the LDCs.

Multilateral Assistance

Both the WTO and UNCTAD produce training courses in WTO dispute settlement.

The WTO Initiatives

The WTO offers a one-week Dispute Settlement Course conduced in English, French and Spanish, open to developing countries, least-developed countries, customs territories and economies in transition which are members is restricted to government officials nominated by their governments.

Apart from providing the participants extensive knowledge on basic principles of the WTO, it engages them in simulation exercises allowing them to further develop their, practical knowledge and sharpen their skills needed to apply at the various stages of dispute settlement.

Another three-week long course titled ‘Introduction to the WTO’, which focuses on issues related to dispute settlement, is also available for government officials from least-developed countries.

The WTO also offers teach-yourself videos tiled, “Case Studies of WTO Dispute Settlement”. The video is available on the WTO web site.

Although WTO does provide technical assistance in terms of intellectual capacity building and funding, these resources are not by themselves sufficient to meet all developing country technical assistance needs despite the fact that there has been remarkable increase in these efforts in recent years.

- Provide legal advice on WTO Law

- Provide support to parties and third parties in WTO dispute settlement proceedings,

- Train government officials in WTO law though seminars on WTO law and jurisprudence, internships and other appropriate means; and

- Perform any other functions assigned to it by the General Assembly.

Some Strategic proposals for Developing Countries

At the Marrakesh Agreement, members agreed to undertake a review of the DSU procedures after four years. Subsequently, in Doha, the Ministerial Meeting did consider the matter but failed to reach any conclusion. Since then, dozens of submissions have been made by developed, developing and least developed countries to bring in necessary amendments in the rules and procedures of the DSU. Though the perception expressed by various groups did differ from one another, it is, however, for the greater interest to take the maximum out of these proposals. Since the aim of the paper is to deal particularly with issues concerning the interest of the LDCs, following is a list of such proposals regarding special and differential treatment for the LDCs:

The following proposals were made with respect to special and differential treatment for LDCs:

- Include the Marrakesh Decision on Measures in Favor of WCs in Annex I so that it is justifiable by the DSU – I.e., LDCs will only be required to undertake commitments and concessions to the extent consistent with their individual development, financial and trade needs, or their administrative and institutional capabilities.

- So that legal experts may be assigned to developing country litigants, the secretariat should maintain a geographically balanced roster of legal experts from which LDcs may select to foully discharge the function of counsel to the LDC party to a dispute, without financial cost to the LDC.

- Parties to a dispute in which and LDC is party should always explore the possibilities of holding consultations in the capital of the LDC party.

- Good offices’ should be automatically offered by the Director General immediately following consultations that did not resolve the matter, with no need for the LDC party to make a request. A developed country complainant shall not request establishment of a panel prior to using ‘good offices’ procedures in good faith.

- The request by a developed country complainant for the establishment of a panel must include a setting out of deu restraint that been taken by the applicant. A panel’s first task will then be to evaluate the complainant’s written account of due restraints that has been taken and the adequacy of efforts expended to reach a mutually agreed solution. If either is found to be inadequate, the matter will be referred to the DSB to make preliminary recommendations and rulings including further use of ‘good offices’ to resolve the matter.

- Article 8; 1 0 should read; When a dispute is between a least developed country Members and a developed country Member the panel shall include at least one panelist from a least developed country Member and, if the least-developed country Member so requests, the panel shall include two panelists from least-developed country Members. [ Equivalent wording is to be included for developing country Members.]

- Panels shall always take full account of special and differential treatment available to [developing country and] least-developed country Members in all applicable WTO agreements, without a need for a party to request it. To this end, the standard terms of reference should be amended to require panels to call for research input of the effects of a negative decision against the LDC [for the developing country’ party.

- The secretariat shall give its work regarding the legal, historical and procedural aspects of the matter in dispute to any LDC party, including third parties, to provide guidance on their specific rights and obligations relating to the matters in dispute.

- Panelists and members of the Appellate Body shall present individual opinions, except that the majority of them may provide a joint opinion. Dissenting opinions will also be circulated.

- When the DSB is adopting recommendations concerning a case involving a [developing or] least-developed party, it shall consider fruther appropriate action, without need for the [developing country or] least-developed party to raise the matter.

- When compliance of a measure is being considered at the panel, AB or arbitration stage, particular attention should be paid to matters affecting the developmental interests of affected LDCs.

- No compensation or retaliation will be approved against LDCs. An LDC respondent will simply be required to withdraw the offending measure. When determining appropriate levels of compensation, account shall be taken of the trade coverage of the inconsistent measure and its impact on the economy and the development prospects of a (developing or] LDC party. When determining compensation for a LDC complainant against a developed respondent, the DSB shall recommend monetary and other appropriate compensation computed from the date of the adoption of the inconsistent measure by the developed respondent to the date the measure is withdrawn. In a case of a LDC complainant and developed country respondent, universal/collective retaliation authority shall be granted to all WTO Members, each to the level of nullification or impairment set for the LDC, unless rejected by consensus. Such authority shall only be granted following an arbitral determination of the appropriate level of compensation, taking account of potential impediments to the attainment of the LDCs development objectives. The arbitrator must also consider whether retaliation under a different agreement by the LDC complainant would be effective without harming the LDC’s interests,