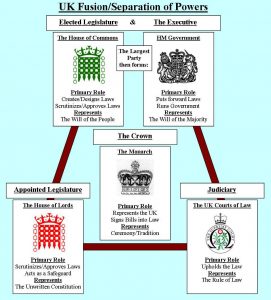

The conception of the separation of powers has been applied to the United Kingdom and the nature of its executive (UK government, Scottish Government, Welsh Government and Northern Ireland Executive), judicial (England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) and legislative (UK Parliament, Scottish Parliament, National Assembly for Wales and Northern Ireland Assembly) functions. Historically, the apparent merger of the executive and the legislature, with a powerful Prime Minister drawn from the largest party in parliament and usually with a safe majority, led theorists to contend that the separation of powers is not applicable to the United Kingdom. However, in recent years it does seem to have been adopted as a necessary part of the UK constitution.

The independence of the judiciary has never been questioned as a principle, although application is problematic. Personnel have been increasingly isolated from the other organs of government, no longer sitting in the House of Lords or in the Cabinet. The court’s ability to legislate through precedent, its inability to question validly enacted law through legislative supremacy and parliamentary sovereignty, and the role of the Europe-wide institutions to legislate, execute and judge on matters also define the boundaries of the UK system.

Separation of Powers in the UK: The UK is one of the most peculiar states in the world. It is one of those few states which do not have a written constitution. Due to the absence of a formal written constitution, it is possible to claim that there is no formal separation of powers in the UK.

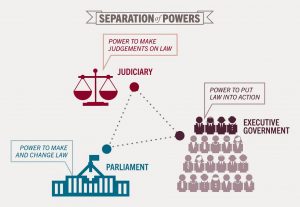

The political doctrine of the Separation of Powers can be traced back to Aristotle, who states: “There are three elements in each constitution …first, the deliberative, which discusses everything of common importance; second the officials; and third, the judicial element.” This highlights the three elementary functions that are required for the organisation of any state. Nowadays, they are defined as the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, and are carried out by Government.

The legislature is the law-making body, and is comprised of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The legislative function involves ‘the enactment of general rules determining the structure and powers of public authorities and regulating the conduct of citizens and private organisations.’

The executive is all the institutions and persons concerned with the implementation of the laws made by the legislature. It involves central and local government and the armed forces. The role of the executive ‘…includes initiating and implementing legislation, maintaining order and security, promoting social and economic welfare, administering public services and conducting the external relations of the state.’

The judiciary is made up mainly of professional judges, and their main function is ‘to determine disputed questions of fact and law in accordance with the law laid down by Parliament and expounded by the courts and …is exercised mainly in the civil and criminal courts.’

The question which now arises is whether or not there should be a strict separation of each of the above functions. Locke stated:

…it may be too great a temptation to human frailty…for the same persons who have the power of making laws, to have also their hands the power to execute them, whereby they may exempt themselves from obedience to the laws they make, and suit the law, both in its making and execution, to their own private advantage.

Similarly, Montesquieu believed that:

When legislative power is united with executive power in a single person or in a single body of the magistracy, there is no liberty…Nor is there liberty if the power of judging is not separate from the legislative power and from the executive power. If it were joined to legislative power, the power over the life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary, for the judge would be the legislator. If it were joined to executive power, the judge could have the force of an oppressor.

All would be lost if the same man or the same body of principal men, either of nobles, or of the people, exercised these three powers: that of making the laws, that of executing public resolutions, and that of judging the crimes or the disputes of individuals.

These statements illustrate that both academics felt if one, or a group of persons, controlled more than one limb, the result would inevitably be corruption and an abuse of power. Tyranny and dictatorship would ensue and this, in turn, would mean a loss of liberty for the people.

However, although each emphasise the importance of a strict separation, it can be seen that in the UK, this is not the case. Parpworth states: ‘a separation of powers is not, and has never been a feature of the UK constitution. An examination of the three powers reveals that in practice they are often exercised by persons which exercise more than one such power.’ Why is this so? Why is there not a strict separation? Saunders explains that: ‘…every constitutional system that purports to be based on a separation of powers in fact provides, deliberately, for a system of checks and balances under which each institution impinges upon another and in turn is impinged upon.’ If there was a strict separation, and we did not have overlaps or checks and balances, our system of Government would become unmoveable. A lack of cooperation between limbs would result in constitutional deadlock and therefore, ‘…complete separation of powers is possible neither in theory nor in practice.’

There are numerous examples of overlap and checks and balances between the three functions of government, and these shall now be explored.

The main instance of overlap, in recent years, was the position of Lord Chancellor. This role has been continually citied to support the view that there is no separation of powers in the United Kingdom.Historically, the position of Lord Chancellor was distinctive in that he was a member of all three branches of Government and exercised all three forms of power. He would sit as speaker in the House of Lords (legislative function), was head of the judiciary (judicial function), and was a senior cabinet minister (executive function). After the Human Rights Act 1998 and the case of McGonnell v UK (2000) , the Government announced changes to the role of Lord Chancellor in the UK. In McGonnell, the European Court of Human Rights held that the Royal Court Bailiff of Guernsey had too close a connection between his judicial functions and his legislative and executive roles and as a result did not have the independence and impartiality required by Article 6(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights 1950. This had implications on the Lord Chancellors role, as he performed very similar functions in the UK.

It was after this that the Government enacted the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, which meant that the Chancellor was replaced as head of the judiciary by the Lord Chief Justice . He was replaced as speaker in the House of Lords by the creation of the post of Lord Speaker , and now only appoints judges on the basis of recommendation from a Judicial Appointments Commission .

These changes show that there is a strong importance still placed upon the doctrine of separation of powers. However it is still possible to see overlaps within the three limbs. Examining the relationship between the legislature and the executive Bagehot stated that there was a close union and nearly complete fusion of these powers. This notion had been criticised, particularly by Amery, who wrote that:

Government and Parliament, however intertwined and harmonized, are still separate and independent entities, fulfilling the two distinct functions of leadership direction and command on the one hand, and of critical discussion and examination on the other. They start from separate historical origins, and each is perpetuated in accordance with its own methods and has its own continuity.

So let us examine this relationship. Firstly, the question to ask is whether the same persons form part of both the legislature and executive. It can be seen that ministers are members of one House of Parliament, but there are limitations as to how many ministers can sit in the House of Commons. As well as this, most people within the executive are disqualified from the Commons. These include those in the armed forces and police and holders of public offices. So it can be seen from this that it is ‘only ministers who exercise a dual role as key figures in both Parliament and the executive.’

The second question is whether the legislature controls the executive or visa versa. The legislature has, in theory, ultimate control as it is the supreme law making body in this country. However in reality, the executive can be seen to dominate the legislature. Government ministers direct the activities of central government department and have a majority in the House of Commons. Lord Halisham, the former Lord Chancellor, has referred to the executive as an elective dictatorship. He means Parliament is dominated by the Government of the day. Elective dictatorship refers to the fact that the legislative programme of Parliament is determined by the government, and government bills virtually always pass the House of Commons because of the nature of the governing party’s majority. However, the legislature has opportunities to scrutinise the executive, and does so during question time, debates and by use of committees.

The final question in this area is whether or not the legislature and executive exercise each other’s functions. It can be seen that the executive performs legislative functions in respect of delegated legislation. Parliament does not have enough time to make all laws and so delegates its power. This is ‘convenient to the executive that ministers and local authorities and departments can implement primary legislation by making regulations.’ However effective parliamentary procedures exist that scrutinise the use made of delegated power which will be discussed below.

The next relationship to be examined is that of the executive and the judiciary, and again, the questions we ask are similar. Firstly, do the same persons form part of the executive and the judiciary? Originally, the executive had the power to appoint judges and the Lord Chancellor sat in the House of Lords. However, following the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, as discussed above, the executive has less control. Judges are now appointed by the Judicial Appointments Committee.

The second question is whether the executive control the judiciary or do the judiciary control the executive. Judicial independence is controlled by law. Since the Act of Settlement 1700, superior judges can only be dismissed by an address from both Houses of Parliament. But the judiciary do exercise some control over the executive. This is via judicial review. Bradley and Ewing state that this is an ‘essential function to protect the citizen against unlawful acts of government agencies and officials’. It involves the courts determining the lawfulness of executive power and is principally concerned with the legality of the decision-making process when delegated legislation is created. This demonstrates a definitive crossover between the judiciary and executive. However, some public bodies are exempt. For example, in R v Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, ex parte Al Fayed (1998) the court of Appeal ruled that the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards could not be subjected to judicial review. This was largely due to the principles of the separation of powers.

The third question is whether or not the executive and judiciary control one another’s functions. Once again, overlap can be seen, with the executive exercising a judicial function through the growth of administrative tribunals which adjudicate over disputes involving executive decisions.

The final relationship to examine is that of the judiciary and legislature, and again, the same questions must be asked. Firstly, do the same persons exercise legislative and judicial functions? To honor the separation of powers, the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 provides that all full time members of the judiciary are barred from membership of the House of Commons. In previous years, the Law Lords from the House of Lords sat in the upper house of the legislature. As a result they: ‘took part, to a limited extent, in legislative business.’ However, since the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, they no longer execute legislative functions due to the newly created Supreme Court, which is separate from the House of Lords.

Secondly, does the legislature control the judiciary or does the judiciary control the legislature. It is a constitutional convention that MP’s should respect judicial independence and not comment on the activities of judges unless there is motion to dismiss a superior judge. Judges, although they may examine acts of the executive to make sure they conform with the law, cannot review the validity of legislation passed by the legislature due to the doctrine of legislative supremacy. They are under a duty to apply and interpret the laws enacted by Parliament. If a Parliamentary Act is in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights, then, under the Human Rights Act 1998, judges in superior courts can make a declaration of incompatibility. However this does not mean the act is not valid, because, again honoring the separation on powers; only the Parliament can make or unmake law.

The final question is whether the legislature and judiciary exercise each other’s functions. ‘Each House of Parliament has the power to enforce its own privileges and to punish those who offend against them’. This once again is an example of overlap. The judiciary, when developing the common law, interpret statutes and delegated legislation. Thus, Bradley and Ewing describe them to have a quasi legislative function. They have a narrow ability to legislate, but their ‘decisions are important as a source of law on matters where the Government is unwilling to ask Parliament to legislate, and …directly affect the formal relationship between the judiciary and Parliament.’

In conclusion, it can be seen there are definite relationships between each limb of government, and this shows that the separation of powers is not a concept to which the United Kingdom fully adheres. However, the view of the courts is one of absolute separation. ‘…it is a feature of the peculiarly British conception of the separation of powers that Parliament, the executive and the courts have their distinct and largely exclusive domain.’ Whilst the courts remain of this view, and whilst the three limbs, although they overlap in many ways, remain distinct and largely separate, we can say there is at least a partial separation of powers in the UK. And rightly, as Parpworth points out: ‘an absolute separation would in practice be counterproductive in that it would prevent the abuse of power by preventing the exercise of power. Government could not operate if this were the case.’ The recent changes to the constitution as a result of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 prove that the concept is still firmly believed in, and while not always respected, it remains something the Munro states should not be ‘lightly dismissed’.